Note: This post was originally published by Luis Natera on his personal blog. It has been republished here as part of TYN Studio's content.

How should we categorize cities? Rather than relying on stereotypes—Amsterdam equals bicycles, Los Angeles equals cars—we can use data-driven methodology to understand cities through their transportation networks.

The Urban Fingerprint Approach

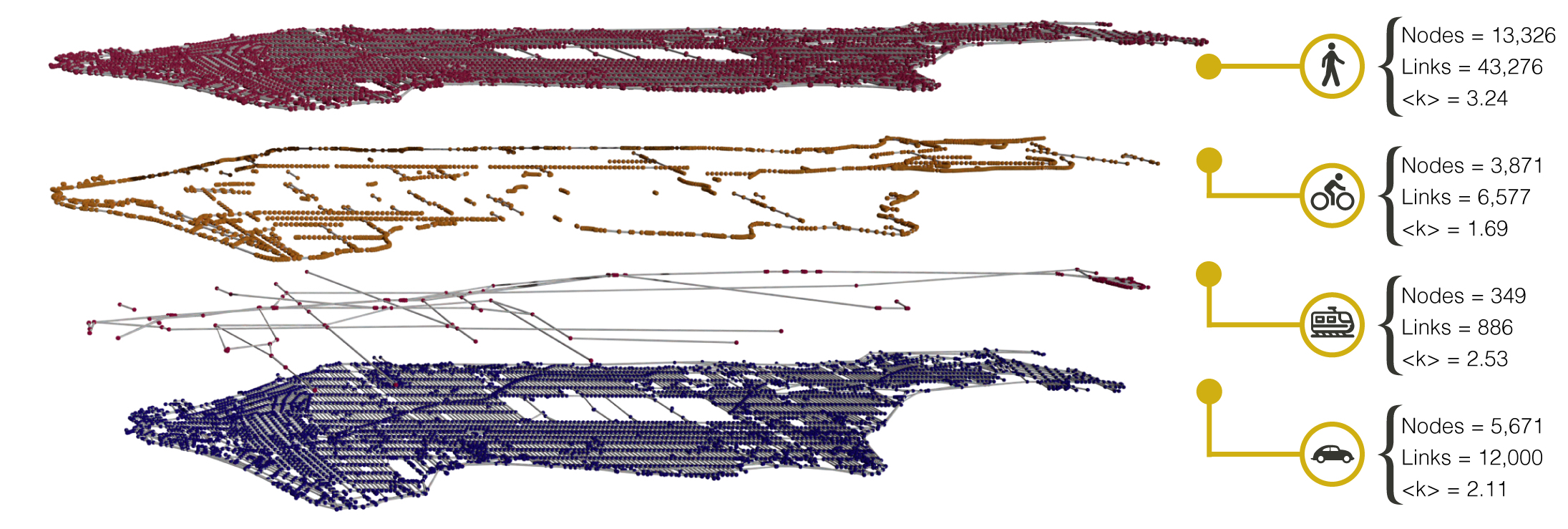

I developed a technique that measures how many intersections across a city are accessible via different transportation modes. The key insight is that in well-integrated cities, transport hubs connect multiple layers—like train stations with bicycle and pedestrian access nearby.

This "urban fingerprint" reveals not just which modes exist, but how they work together. A city might have both bike lanes and subway lines, but if they don't connect, you have two separate systems rather than an integrated network.

Analyzing Fifteen Global Cities

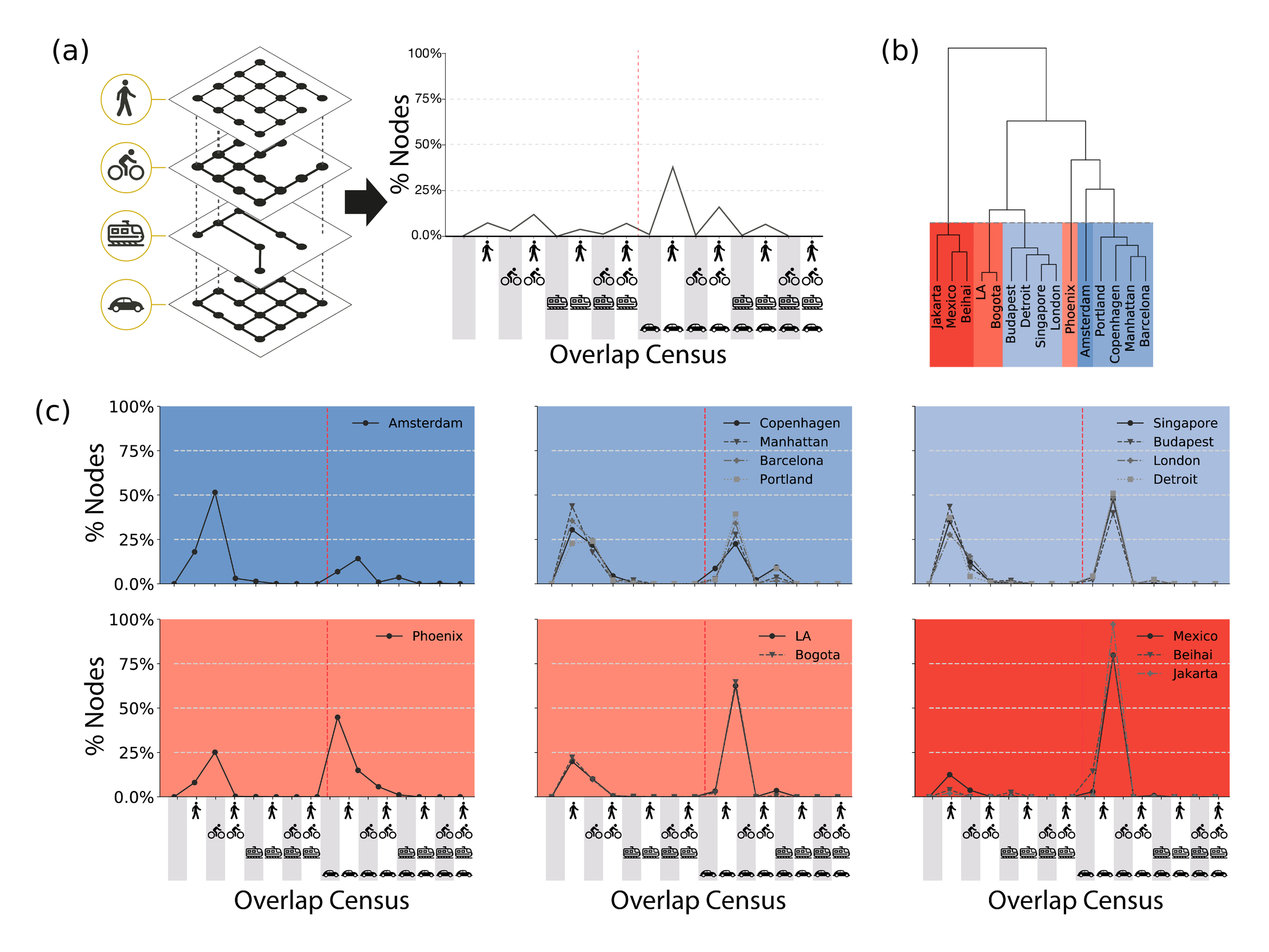

Using k-means clustering on infrastructure data, I identified six distinct city types based on multimodal infrastructure patterns. The analysis reveals patterns that go beyond simple "bike-friendly" or "car-dependent" labels.

The concentration of nodes in one layer or one configuration informs not only about the mobility character of the city, but also unveils the importance of explicitly considering overlooked layers—particularly walking and cycling infrastructure.

The Six City Clusters

Cluster 1 - Amsterdam: The outlier. Extensive bicycle infrastructure that integrates seamlessly with walking and transit.

Cluster 2 - Copenhagen, Manhattan, Barcelona, Portland: Cities prioritizing active mobility with good integration between walking, cycling, and transit.

Cluster 3 - Budapest, London: European cities with strong transit but more fragmented cycling infrastructure.

Cluster 4 - Los Angeles, Bogota, Mexico City: Car-centric cities with limited non-automobile options.

Cluster 5 - Beihai, Jakarta: Rapidly developing cities with automobile-focused growth.

Cluster 6 - Detroit: Extreme car dependence with minimal alternative infrastructure.

Beyond Stereotypes

The analysis reveals surprises. Manhattan clusters with Copenhagen—not because they look similar, but because they share strong pedestrian and transit integration. Portland clusters with Barcelona, showing similar patterns of multimodal connectivity despite vastly different climates and cultures.

Meanwhile, some cities we think of as "progressive" show significant gaps. London has excellent transit but fragmented cycling infrastructure. Mexico City's subway system doesn't integrate well with walking and cycling networks.

Implications for Planning

This analytical framework helps urban planners:

- Identify best practices: See which cities successfully integrate multiple modes

- Spot gaps: Find where infrastructure exists but doesn't connect

- Set priorities: Understand which improvements would have the most impact

- Learn from peers: Compare with cities facing similar challenges

The key insight is that successful urban mobility isn't just about having bike lanes or transit—it's about how different modes connect and integrate. A city's "fingerprint" reveals whether it's designed as a coherent multimodal system or a collection of separate, disconnected networks.

Data-Driven Decision Making

Rather than copying what worked in Amsterdam or Copenhagen, cities can use this analysis to understand their current state and identify specific improvements. Where are the gaps? Which connections are missing? What would provide the most value?

The urban fingerprint approach moves the conversation from ideology to evidence, from assumptions to data. It shows us not just where cities are, but where they could go.