Note: This post was originally published by Luis Natera on his personal blog. It has been republished here as part of TYN Studio's content.

How often does it happen that while driving a car the street disappears or gets merged into a sidewalk? It really doesn't happen, right?

But with cycling infrastructure, this is the norm. Bike lanes frequently terminate abruptly, merge into regular streets, or simply end with no clear continuation. This fragmentation is one of the biggest barriers to widespread cycling adoption—and we can measure it.

The Fragmentation Problem

Driving networks are connected by design. You can drive from almost any point to any other point in a city without leaving the road network. But bicycle infrastructure rarely works this way.

Even in bike-friendly cities, the infrastructure often consists of disconnected segments. You might have a protected bike lane for two kilometers, then nothing, then another segment elsewhere. This forces cyclists to either:

- Mix with car traffic (reducing safety and comfort)

- Use sidewalks (creating pedestrian conflicts)

- Find alternative routes (increasing travel time)

Measuring Fragmentation with Python

We can analyze bicycle network connectivity using Python, OSMnx, and NetworkX. Here's how:

1. Configure OSMnx to Capture Bicycle Infrastructure

import networkx as nx

import osmnx as ox

# Include bicycle-specific tags in the download

ox.config(

use_cache=True,

useful_tags_way=ox.settings.useful_tags_way + ["bicycle"]

)

2. Download and Extract the Bike Network

def bike_network(city: str) -> nx.Graph:

# Download complete street network

G = ox.graph_from_place(

city,

network_type="all",

simplify=False,

which_result=1

)

# Filter to only bicycle infrastructure

non_cycleways = [

(u, v, k) for u, v, k, d in G.edges(keys=True, data=True)

if not ('cycleway' in d or

'bicycle' in d or

'cycle lane' in d or

'bike path' in d or

d['highway'] == 'cycleway')

]

G.remove_edges_from(non_cycleways)

G = ox.simplify_graph(G)

return ox.project_graph(G)

This extracts only the edges that are specifically marked as bicycle infrastructure—protected bike lanes, cycle tracks, dedicated bike paths, etc.

3. Count Network Components

# Analyze connectivity

bike_components = len([

c for c in nx.connected_components(nx.to_undirected(G_bike))

])

print(f"The city of {city} has {bike_components} different bicycle components")

Each "component" is a separate, disconnected part of the network. Ideally, you'd want one large component where you can reach any part of the bike network from any other part.

4. Compare with Driving Network

# Download driving network for comparison

G_drive = ox.graph_from_place(

city,

network_type="drive",

simplify=True,

which_result=1

)

G_drive = ox.utils_graph.remove_isolated_nodes(G_drive)

G_drive = ox.project_graph(G_drive)

5. Visualize Both Networks

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import geopandas as gpd

# Convert to GeoDataFrames

bike_edges = ox.graph_to_gdfs(G_bike, nodes=False)

drive_edges = ox.graph_to_gdfs(G_drive, nodes=False)

# Create visualization

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(16, 9), facecolor="#F8F8F8")

ax.set_facecolor("#F8F8FF")

# Plot driving network in blue

drive_edges.plot(

ax=ax,

linewidth=0.25,

color="#003366",

zorder=0,

alpha=1

)

# Plot bike network in pink

bike_edges.plot(

ax=ax,

linewidth=1,

color="#FF69B4",

zorder=1

)

The Results

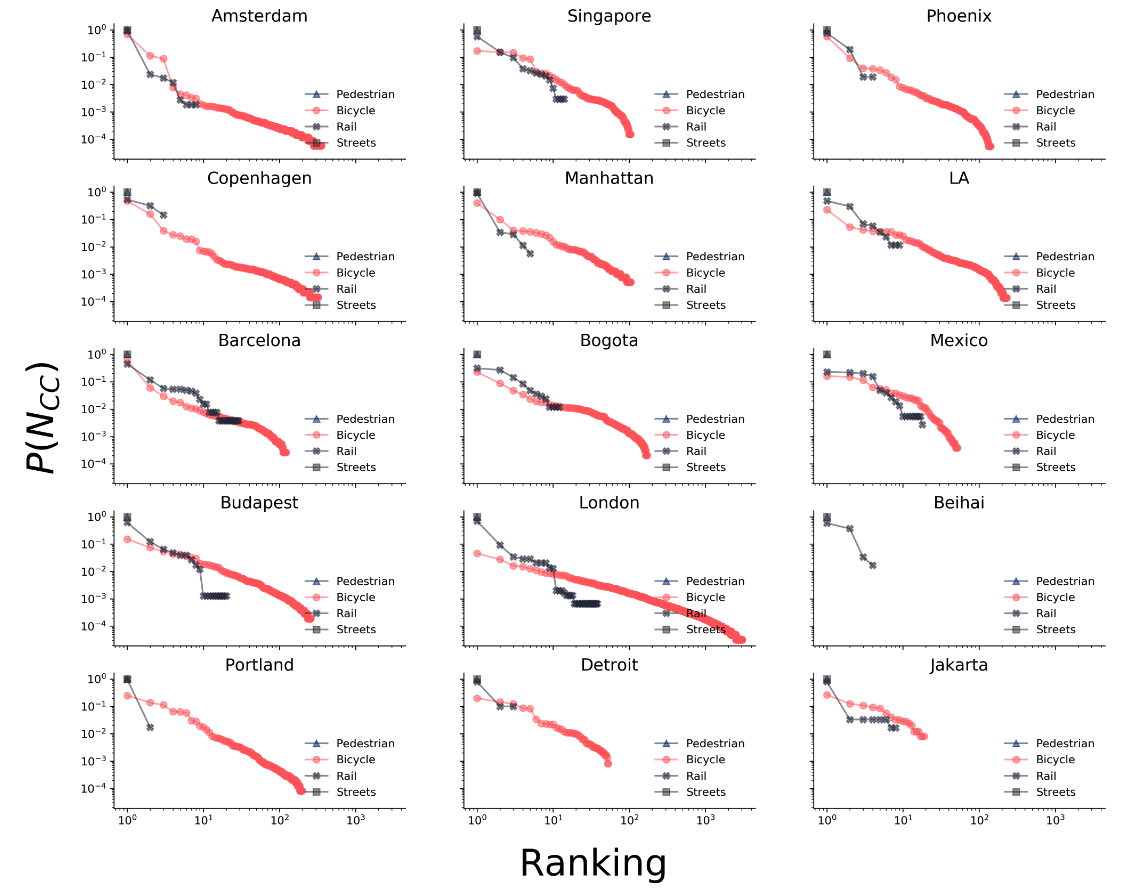

Amsterdam, often considered one of the world's most bike-friendly cities, has 282 separate bicycle network components. London? Approximately 3,000 components.

This fragmentation reveals a harsh reality: even cities investing heavily in cycling infrastructure often create disconnected pieces rather than coherent networks.

Why This Matters

Research from "Data-driven strategies for optimal bicycle network growth" shows that most analyzed cities have highly fragmented cycling infrastructure. This has real consequences:

- Safety: Disconnections force cyclists into car traffic

- Accessibility: You can't reach all destinations by bike

- Adoption: People won't cycle if the route is dangerous or inconvenient

- Equity: Fragmentation often leaves some neighborhoods completely disconnected

From Measurement to Action

Understanding fragmentation helps cities prioritize infrastructure investments. Instead of adding random bike lanes where politically convenient, planners can:

- Connect existing fragments: Identify short gaps that separate large networks

- Prioritize strategic links: Find connections that would serve the most people

- Build networks, not lanes: Think about overall connectivity, not just individual segments

- Measure progress: Track component count and network size over time

The Path to Connected Networks

A truly bike-friendly city isn't just one with lots of bike lanes—it's one where those lanes form a coherent, connected network. You should be able to bike from any part of the city to any other part on safe, dedicated infrastructure.

Python and network analysis give us the tools to measure this, identify gaps, and plan improvements strategically. The data shows us clearly: we're not there yet. But now we know exactly what needs to be fixed.